Conservation Community Should Care About Violent Extremism, Urges GEOG Researcher

In a new perspective piece co-authored by GEOG Associate Professor Meredith Gore, conservation experts draw attention to the devastating impacts that violent extremism can have on protected areas and the vital role that the conservation community can play in times of conflict.

“People don’t usually think of conservation science and violent extremism as being linked, but the conservation community could really be paying more attention to the changing dynamics on the ground in protected areas, especially when it comes to violent extremism,” said Gore, a conservation criminologist who studies the human dimensions of global environmental change.

Increasing violent extremism spillover into protected areas poses a threat to some of the world’s greatest biodiversity strongholds. When violent conflict spirals out of control, local communities can be forced to flee and take shelter, natural resources can fall under the control of extremist groups, wildlife populations can collapse and conservation programs can cease due to heightened security risks and inaccessibility to protected areas.

“It’s at these times of conflict, when many from the international community typically withdraw, that they can actually be the most helpful on the ground and monitor what’s happening in terms of environmental change,” said Gore.

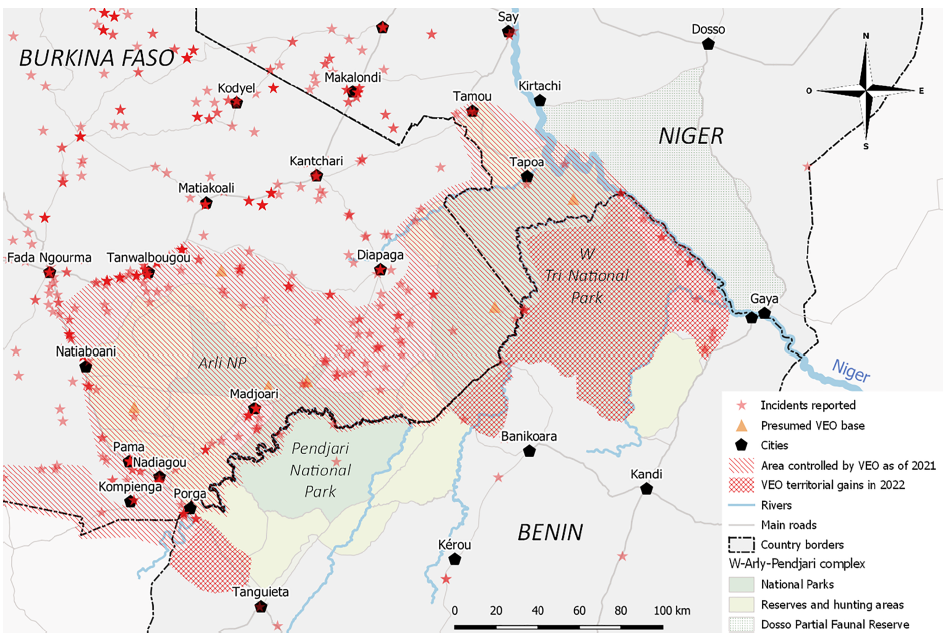

In the paper, the authors highlighted a particularly urgent situation at the border of Burkina Faso, Niger, and Benin where violent extremists have taken over 62% of the W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) complex of protected areas—the largest refuge for forest elephants and other large mammals in West Africa. Without scientists in the field, conservation groups have limited knowledge of the ongoing social, political and environmental changes in the region. The scarce available data suggest an ecosystem on the verge of collapse and an alarming decrease in elephant populations.

“This is the last stronghold of forest elephants in this part of the world,” said Gore, who warned that this case of violent extremism may reverse conservation progress, lead to extinctions and cause a cascade of negative consequences for the environment and society.

To address the dire situation in the WAP complex and other protected areas in the world, the authors outlined several recommendations for how the conservation community can take a proactive role in conflict-ridden areas. According to Gore, continued engagement with local communities is key. “[Locals] are uniquely impacted by these situations and they have unique perspectives, sometimes offering the most sustainable or feasible solutions.”

Another important role for conservation scientists is continued on-the-ground monitoring, which helps keep research afloat and provides insight into conflicts as they emerge. “By keeping eyes and ears to the ground, [the conservation community] can help prevent the spark of lower-level conflicts into higher-level conflicts, instead of just responding to major conflicts after they occur,” said Gore.

Gore also underscored the power of combining data from multiple sources, especially in the face of restricted access to protected areas. To get a clearer picture of the situation in the WAP complex, the authors pulled together data from public and private databases and field personnel to map out violent extremist territories across the region. "Integrating data across sources is key to tracking global environmental change,” said Gore.

With sustained funding and support from the international conservation science and policy community, conservation efforts may have a chance at survival. “The example in the article is a frightening call to what’s happening in a really special place in the world,” concluded Gore.

Read the paper here.

Photo by David Clode on Unsplash

Published on Tue, 10/25/2022 - 12:18